Designing for rational decision makers is designing for an audience that doesn’t exist. How can our understanding of cognitive biases help us build experiences that users will love?

Loss. It’s a four-letter word with more power over your decision making than you may know.

A Cal State San Marcos professor studying motivation turned his classroom into a real-world user lab in order to measure just how powerful the idea of loss is. The experiment was a simple one: he offered his students the opportunity to skip the final exam by earning points over the course of the semester. He divided his test subjects into two classes, making them the exact same offer, but using slightly different phrasing:

“In the first class, the students were told that the final exam was required but they could earn the right to not take it with five points from the quizzes. In the second class however, they were told that the final exam was optional. But, they could lose that right if they did not get five points from the quizzes.”

The difference? Opting out of the final was presented as either a privilege to be gained or an opportunity to be lost.

At the end of the semester, the results came back. 43% of students in the first class had met the requirements for skipping the final via earning, while a whopping 82% in the second class had qualified via loss aversion.

That’s how powerful loss is.

Cognitive Biases

This experiment focused on the much-documented cognitive bias known as loss aversion or “the human tendency to strongly prefer avoiding a loss to receiving a gain. This particular cognitive bias consistently explains why so many of us make the same irrational decisions over and over, in the realm of economics and elsewhere.”

The power of loss aversion runs counter to everything that our logical minds tell us to be true, but it’s just one cognitive bias. There are 165 known others that affect our decision making every day. So where do cognitive biases come from, and how do they so profoundly impact our capacity for logical decision making?

Cognitive biases are the result of our brains’ attempts to process the onslaught of information our senses are constantly bombarded by. Without the ability to filter and prioritize this information, we’d be overwhelmed and find ourselves in a perpetual state of paralysis. Even when considering important, complex decisions, we are unable to weigh all the information available to make educated choices. In fact, neuroscientists have discovered that patients with damage to the part of the brain affected by cognitive biases are unable to make even simple decisions.

Cognitive biases can be grouped into four categories:

|

| For a full list of cognitive biases, see Wikipedia. |

One Brain; Two Systems

We all know this theory: the analysts, mathematicians, and scientists of the world rely largely on the logical left half of the brain, while artists, writers, and innovative thinkers are plugged in to the creative, right hemisphere. You can take quizzes online to find out what kind of thinker you are, or read books on how to tap into the potential of the other half of your brain.

The problem with this theory is that it isn’t actually true. The idea that people predominantly use one hemisphere of the brain has been widely disproven over the last few decades.

What has emerged as an accurate model of how we think is often referred to as System 1 and System 2, and it is far less understood.

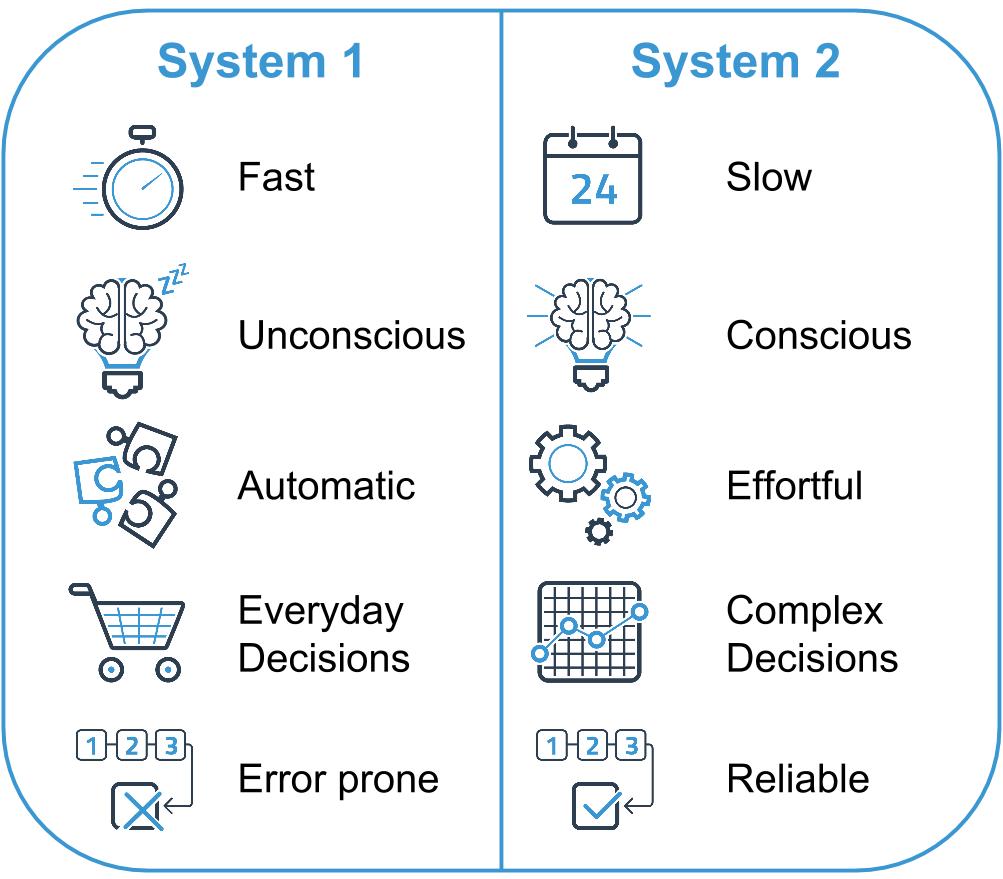

System 1 and System 2 are two distinct modes of thinking that everyone uses every day. System 1 is defined as automatic, autonomous and efficient. It is the home of intuition and emotion and often operates on a subconscious level. It is sometimes referred to as the stranger within, since it’s workings are largely hidden from us, and it is the mode of thinking prone to cognitive biases. System 2 is a processing powerhouse that consumes a great deal of energy. It’s a slow and controlled tool that utilizes logic and deduction. If you’ve ever tried to solve a tricky problem while walking and you’ve stopped in your tracks, it’s because System 2 literally can’t spare the processing power to handle both tasks at the same time.

|

So, how do System 1 and System 2 divvy up the workload of everyday decision making? That’s where things get interesting. Scientists studying these two types of thinking have estimated that up to 90% of our decisions are made by System 1. Other research involving brain imaging suggests that we actually make decisions up to 5 seconds before our conscious mind becomes aware of them. Further complicating matters is that System 1 will invoke System 2 in justifying irrational decisions; when someone is asked to explain a decision made using System 1, System 2 will invent a logical, if false, rationalization for that choice. This all happens at a subconscious level, leaving us with the incorrect belief that our decision making is rational.

Fooled by User Testing

Understanding the role of System 1 makes it easy to see the potential pitfalls of current UI/UX methodologies, which rely heavily on user research. When asked a series of questions in a lab environment about decision making, preferences, and predictions of future behavior, test users will inevitably give logical, rational answers that they believe to be absolutely true. And then they will go into the real world, where they’ll make actual decisions using criteria heavily influenced by cognitive biases and intuition.

We too often equate lab-based, System 1 user insights with real world, System 2 intuition.

Let’s look at another example, one involving the paradox of choice. Universally, when asked if more choice (i.e. more freedom) will result in more or less happiness, people will predict that more choice equals more happiness. Yet research has shown that the exact opposite is often true. Harvard researcher Dan Gilbert recently conducted a study on this paradox that he detailed in his latest TED talk. In the study, two groups of students first participated in a course in which they learned black and white photography. At the end of the course they were presented with two of their finished pieces but told that they keep only one. Each group was told that they could choose which photo to keep, but the first group was told that their decision was irrevocable, while the second was told that they could change their decision at any time.

When Gilbert followed up over the next several weeks, he found that the students in the first group–the ones who had made the irrevocable decision–were much happier with their choice than those in the second group. Why? The results of this study highlight the power of a phenomenon known as choice supportive bias. Once an irrevocable decision has been made, our minds set out to justify the decision in an effort to put the choice behind us and move on to the next question. An open-ended choice has no such resolution. Without it, our minds tend to ruminate and are nagged by doubt. In the photography experiment, the happiness of the second group of students was marred by their questioning of their choice’s validity.

These are just two examples of the influence that System 1 has on our thinking, but you get the idea. We are all irrational beings, prone to making decisions through intuition rather than logic. But how can designers take this into account when creating user experiences?

Designing for the Everyday Brain

Examples of behavioral design in action are everywhere if you know what you’re looking for. Maybe you’ve heard of streaks, a phenomenon that has gotten a lot of recent attention due to the influence it has on Snap Chat users, particularly teenagers. At its core, the streak is just documentation of how many consecutive times a users does something, in this case interacting with a friend. There is no real value in the streak. As one review attempts to describe the snapstreak:

“The ‘point’ of a snapstreak is really just to see how long you can keep it going; it’s one of a few features built into the app that turns it into a kind of game. There’s not exactly anything to ‘win,’ though, so perhaps ‘challenge’ is a slightly better term for a snapstreak than ‘game.'”

While not particularly compelling in writing, the effects of the streak are very real, and are now receiving national attention from concerned parents and psychologists alike.

Before you dismiss the effectiveness of streaks on anyone over the age of 16, you should take a look at these apps: streaksapp.com, habitbull.com, goodtohear.co.uk. Streaks are being built into the foundation of fitness, savings, and even meditation apps because the powerful combination of cognitive biases driving the streak phenomenon can make a huge difference in user behavior. What’s in this magical concoction? Our old acquaintance loss aversion is a main ingredient. The loss, as evidenced by the Snapchat example, doesn’t have to a loss with any real value or consequence to be effective. It simply has to have meaning to us. In addition to loss, a collection of biases like the Zeigarnik Effect make us innately want to complete things we’ve already invested time and energy in. Together, these biases can help encourage us to save for retirement, run a marathon, or waste another couple of hours on social media.

As G.I. Joe once said, knowing is half the battle, and as designers, knowing the importance of cognitive biases can help us design more effective experiences. Objective data we collect from user labs and interviews is only part of the equation.

Relying purely on data can result in experiences that test wonderfully in research environments and fall flat in the real world.

Even a rudimentary understanding of cognitive biases can give us a richer understanding of our users and what drives their decision making. Knowing that unconscious influences like loss aversion and choice-supportive bias are always present, we can make small changes that result in huge differences in things like user engagement, adoption, and retention. A great resource for learning more about cognitive biases is the You Are Not So Smart blog and podcast.

Another invaluable tool is learning more about motivational theory and the types of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards that compel us to action. There are a number of different models out there. Yu-kai Chou, a gamification and behavioral design expert, has created a comprehensive model called Octalysis that defines 8 core human drives.

One final word of caution: when you’re designing experiences with System 1 in mind, be careful not to overestimate your own knowledge of the workings of your users’ minds. That one’s called the illusion of asymmetric insight, and you’ll find it between the telescoping effect and the illusion of external agency on the list of cognitive biases.

Now that you are more aware of cognitive biases, what will you design for the everyday brain?